In this earlier post, we learned how to create a Vector Store in Oracle from LangChain, the hugely popular Python library for working with Generative AI and Large Language Models. We populated it with a little data and then performed some simple vector similarity searches.

In this post, let’s expand on that to implement basic Retrieval Augmented Generation!

First, let’s talk about some concepts – if you alread know this, feel free to jump ahead!

Generative AI – This is a type of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that uses a specialized form of machine learning model, called a Large Language Model (or “LLM”), to create (“generate”) new content based on a prompt from a user. It works by looking at the “tokens” that it received in the input (the “prompt”) and then figuring out what is the most probable next token in the sequence. What is a token? Well, it may be a word, or a part of a word, but we use the word “token” because it could also be part of an audio file or an image, since some of these models support other types of data, not just text. Note that it only generates one token at a time – you have to “run” the model again for every subsequent token.

Training – these models are “trained” by exposing them to very large amounts of data. Usually the data is publicly available information, collected from the Internet and/or other repositories. Training a model is very expensive, both in terms of time, and in terms of the cost of running the specialized GPU hardware needed to perform the training. You may see a model described as having “70 billion parameters” or something like that. Training is basically a process of tuning the probabilities of each of these parameters based on the new input.

When a model sees a prompt like “My Husky is a very good” it will use those probabilities to determine that comes next. In this example, “dog” would have a very high probability of being the next “token”.

Hyper-parameters – models also have extra parameters that control how they behave. These so-called “hyper-parameters” include things like “temperature” which controls how creative the model will be, “top-K” which controls how many options the model will consider when choose the next token, and various kinds of “frequency penalties” that will cause the model to be more or less likely to reuse/repeat tokens. Of course these are just a few examples.

Knowledge cut-off – an important property of LLMs is that they have not been exposed to any information that was created after their training ended. So a model training in 2023 would not know who won an election held in 2024 for example.

Hallucination – LLMs tend to “make up an answer” if they do not “know” the answer. Now, obviously they don’t really know anything in the same sense that we know things, they are rworking with probabilities. But if we can anthropomorphize them for a moment, they tend to “want” to be helpful, and they are very likely to offer you a very confident but completely incorrect answer if they do not have the necessary information to answer a question.

Now, of course a lot of people want to use this exciting new technology to implement solutions to help their customers or users. ChatBots is a prime example of something that is frequently implemented using Generative AI these days. But, of course no new technology is a silver bullet, and they all come with their own challenges and issues. Let’s consider some common challenges when attempting to implement a project with Generative AI:

- Which model to use? There are many models available, and they have all beeen trained differently. Some are specialized models that are trained to perform a particular task, for example summarizing a document. Other models are general purpose and can perform different tasks. Some models understand only one language (like English) and others understand many. Some models only understand text, others only images, others video, and others still are multi-modal and understand various different types of data. Models also have different licensing requirements. Some models are provided as a service, like a utility, where you typically pay some very small amount per request. Other models are able to be self-hosted, or run on your own hardware.

- Privacy. Very often the data that you need for your project is non-public data, and very often you do not want to share that data with a third-party organization for privacy reasons, or even regulatory reasons, depending on your industry. People are also very wary about a third-party organization using their non-public data to train future models.

- How to “tune” to models hyper-parameters. As we discussed earlier, the hyper-parameters control how the model behaves. The settings of these parameters can have a significant impact on the quality of the results that are produced.

- Dealing with knowledge cut-off. Giving the model access to information that is newer than when it was trained is also a key challenge. Probably the most obvious way to do this is to continue to model’s training by exposing it to this newer information. This is known as “fine-tuning”. The key challenge is that is an extremely expensive enterprise, requiring specialized GPU hardware and very highly skilled people to plan and run the training.

Enter “Retrieval Augmented Generation,” (or “RAG”) first introduced by Patrick Lewis et al, from Meta, in the 2020 paper “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks“. RAG is a technique that gives LLMs access to non-public information and/or information created after their training and is orders of magnitude less expensive than fine-tuning.

The essence of RAG is to provide the LLM with the information that it needs to answer a question by “stuffing” that information into the LLM’s “context window” or “prompt” along with the actual question. It’s a bit like an open-book test. Imagine you get a question like this:

How much does a checking account from (some bank) cost? And let’s assume that information is not readily available on the Internet. How would you come up with the answer? You likely could not.

But if the question was more like this:

How much does a checking acount from (some bank) cost?

To answer this question, consult these DOCUMENTS:

(here there would be the actual content of those documents that provide the information necessary to answer that question)Much easier right? That’s basically what RAG is. It provides the most relevant information to the LLM so that it can answer the question.

So now, the obvious questions are – where does it get this information from, and how does it know which parts are the most relevant?

This is where our Vector Store comes in!

The set of information, the non-public data that we want the LLM to use, we call that the “corpus”. Very often the corpus will be so large that there is no reasonable way for us to just give the LLM the whole thing. Now, as I am writing this in May 2025, there are models that have very large “context windows” and could be given a large amount of data. Llama 4 was just released, as I write this, and has a context window size of 10 million tokens! So you could in fact give it a large amount of information. But models that were released as recently as six or twelve months ago have much smaller context windows.

So the approach we use is to take the corpus, and split it up into small pieces, called “chunks” and we create an “embedding vector” for each of these chunks. This vector is basically an n-dimensional numerical representation of the semantic meaning of the chunk. Chunks with similar meanings will have similiar (i.e., close) vectors. Chunks with different meanings will have vectors that are futher apart.

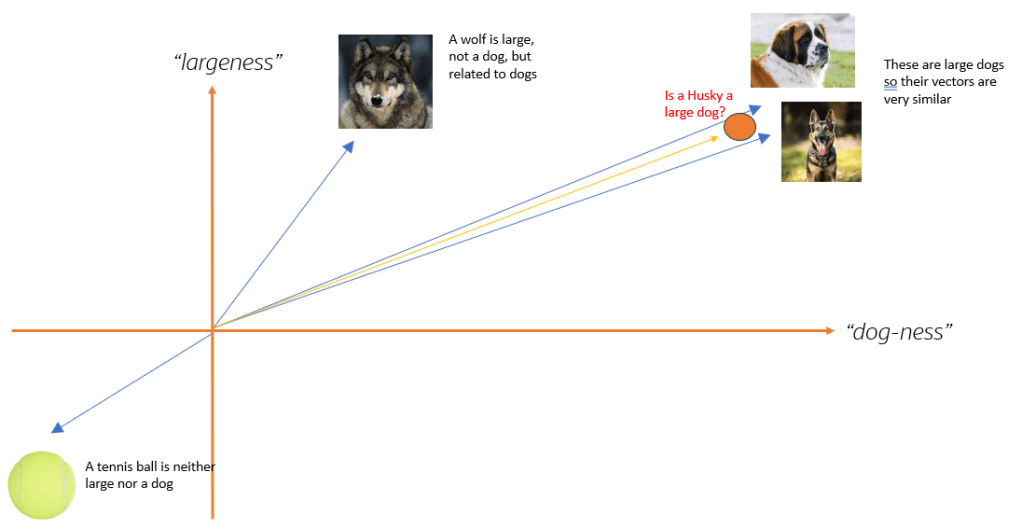

Now, visualizing an n-dimensional vector is challenging. But if n=2, its a lot easier. So let’s do that! Remember, in real models, n is much more likely to be in the thousands or tens of thousands, but the concepts are the same. Consider the diagram below:

In this diagram, we have only two dimensions, the vertical dimension is “largeness” – how large (or small) the thing is. The horizontal dimension is “dog-ness” – how much the thing is (or is not) a dog.

Notice that both the Saint Bernard and the German Shephard (I hope I got those breeds right!) are large dogs. So the vector for both of them are high on both axes, and their vectors are very close together, because in this two-dimensional world, they are indeed very, very similar. The wolf is also large, but it is not actually a dog. Dogs are related to (descended from) wolves, so it is somewhat dog-like, but its vector is quite a distance away from the actual large dogs.

Now, look at the tennis ball! It is not large, and it is not a dog, so it’s vector is almost in the complete opposite direction to the large dogs.

Now, consider the question “Is a Husky a large dog?”

What we do in RAG, is we take that question, and turn that into a vector, using the exact same “embedding model” that we used to create those vectors we just looked at above, and then we see what other vectors are close to it.

Notice that the resulting vector, represented by the red dot, ended up very close to those two large dogs! So if we did a similarity search, that is, if we found the closest vectors to our question vector, what we would get back is the vectors for the Saint Bernard and the German Shephard.

Here’s a diagram of the RAG process:

So we take the question from the user, we turn it into a vector, we find the closest vectors to that in our corprus, and then we get the actual content that those vectors was created from and give that information to the LLM to allow it to answer the question. Remember, in real life there are many more dimensions, and they are not going to be some concept that we can neatly label, like “largeness”. The actual dimensions are things that are learned by the model over many billions of iterations of weight adjustments as it was exposed to vast amounts of data. The closest (non-mathematical) analogy I can think of is Isaac Asimov’s “positronic brain” in his Robots, Empire and Foundation series which he described as learning through countless small adjustments of uncountable numbers of weights..

Wow! That was a lot of theory! Let’s get back to some code, please!

In the previous post, we populated our vector store with just three very small quotes from Moby Dick. Now, let’s use the entire text!

Here’s the plain text version: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701.txt

Here’s the same book in HTML, with some basic structure like H2 tags for the chapter headings: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701-images.html

Let’s create a new notebook. If you followed along in the previous post, you can just create a new notebook in the same project and choose the same environment/kernel. If not, create a new project, then create a notebook, for example basic-rag.ipynb and create a kernel:

Click on the Select Kernel button (its on the top right). Select Python Environment then Create Python Environment. Select the option to create a Venv (Virtual Environment) and choose your Python interpreter. I recommend using at least Python 3.11. This will download all the necessary files and will take a minute or two.

If you created a new environment, install the necessary packages by creating and running a cell with this content. Note that you can run this even if you have a pre-existing environment, it won’t do any harm:

%pip install -qU "langchain[openai]"

%pip install oracledb

%pip install langchain-community langchain-huggingfaceNow, create and run this cell to set your OpenAI API key:

import getpass

import os

if not os.environ.get("OPENAI_API_KEY"):

os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = getpass.getpass("Enter API key for OpenAI: ")

from langchain.chat_models import init_chat_model

model = init_chat_model("gpt-4o-mini", model_provider="openai")

model.invoke("Hello, world!")Paste your key in when prompted (see the previous post if you need to know how to get one) and confirm you got the expected response from the model.

Note: You could, of course, use a different model if you wanted to. See the LangChain model documentation for options.

Now, let’s connect to the database by creating and running this cell (this assumes that you started the database container and created the user as described in the previous post!)

import oracledb

username = "vector"

password = "vector"

dsn = "localhost:1521/FREEPDB1"

try:

connection = oracledb.connect(

user=username,

password=password,

dsn=dsn)

print("Connection successful!")

except Exception as e:

print("Connection failed!")Ok, now we are ready to read that document and create our vector embeddings. But how? In the previous post we manually created some excerpts, but now we want to read the whole document.

Enter Document Loaders! Take a look at that page, LangChain has hundreds of different document loaders that understand all kinds of documetn formats.

Let’s try the basic web loader, create and run this cell to install it:

%pip install -qU langchain_community beautifulsoup4Now create and run this cell to initialize the document loader:

from langchain_community.document_loaders import WebBaseLoader

loader = WebBaseLoader("https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701-images.html")Now load the documents by running this cell:

docs = loader.load()If you’d like, take a look at the result, by running this cell:

docs[0]Well, that is just one big document, that is not so helpful, we want to split that document up into smaller chunks so we can create vectors for each smaller part. Let’s use a document splitter instead.

Install a splitter by running this cell:

%pip install -qU langchain-text-splittersNote: Check out this page for more information about the available splitters. We are going to use the HTMLHeaderTextSplitter. Run this cell:

from langchain_text_splitters import HTMLHeaderTextSplitter

url = "https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701-images.html"

headers_to_split_on = [

("h1", "Header 1"),

("h2", "Header 2"),

("h3", "Header 3"),

("h4", "Header 4"),

]

html_splitter = HTMLHeaderTextSplitter(headers_to_split_on)

html_header_splits = html_splitter.split_text_from_url(url)Let’s see what that did, run this cell:

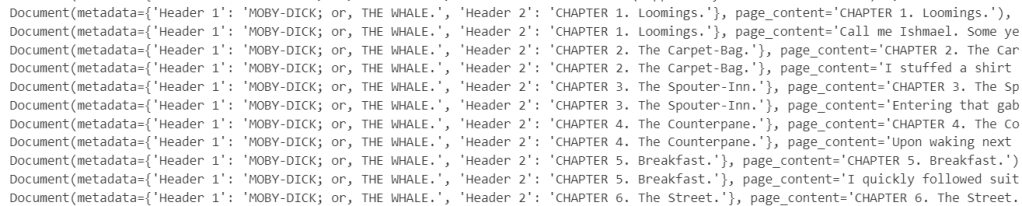

html_header_splitsYou’ll see a long list of Documents and if you look carefully, you can see that it has maintained the structure information.

Great! That’s a lot better.

Now, let’s suppose we wanted to constrain the size of the chunks. Some of those might be too big, we might want to split them even further. We can do that with a RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter.

Let’s say we wanted chunks no bigger than 500 characters, with an overlap of 30. Now this might not be a good idea, but just for the sake of the example, let’s do it by running this cell:

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

chunk_size = 500

chunk_overlap = 30

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=chunk_size, chunk_overlap=chunk_overlap

)

# Split

splits = text_splitter.split_documents(html_header_splits)You can take a look at a few of the chunks by running this cell:

splits[80:85]Ok, great! Next, we need to create our embeddings and populate our vector store.

Install the dependencies, if you have not already, by running this cell:

%pip install langchain-community langchain-huggingfaceAnd let’s create the vector store! Run this cell:

from langchain_community.vectorstores import oraclevs

from langchain_community.vectorstores.oraclevs import OracleVS

from langchain_community.vectorstores.utils import DistanceStrategy

from langchain_core.documents import Document

from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

embedding_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(model_name="sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2")

vector_store = OracleVS.from_documents(

splits,

embedding_model,

client=connection,

table_name="moby_dick_500_30",

distance_strategy=DistanceStrategy.COSINE,

)We are using the same model as we did in the previous post, but now we are passing in our splits that we just created – our 500 character long chunks of our larger chunks created from the HTML document respecting the document structure. And we called our vector store table moby_dick_500_30 to make it a little easier to remember what we put in there.

After that cell has finished (it might take a few minutes), you can take a look to see what is in the vector store by running this command in your terminal window:

docker exec -i db23ai sqlplus vector/vector@localhost:1521/FREEPDB1 <<EOF

select table_name from user_tables;

describe documents_cosine;

column id format a20;

column text format a30;

column metadata format a30;

column embedding format a30;

set linesize 150;

select * from moby_dick_500_30

fetch first 3 rows only;

EOFYou should get something similar to this:

Let’s try our searches again, run this cell:

query = 'Where is Rokovoko?'

print(vector_store.similarity_search(query, 1))

query2 = 'What does Ahab like to do after breakfast?'

print(vector_store.similarity_search(query2, 1))You can change that 1 to a larger number now, since you have many more vectors, to see what you get!

Ok, now we have all the pieces we need and we are ready to implement the RAG!

The most basic way to implement RAG is to use a “retriever” – we can grab one from our vector store like this:

retriever = vector_store.as_retriever()Try it out by asking a question:

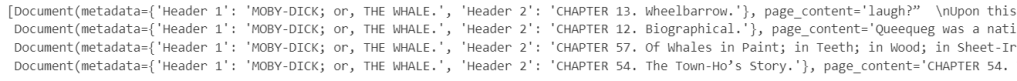

docs = retriever.invoke("Where is Rokovoko?")

docsYou’ll get something like this:

Nearly there!

Now, we want to give the LLM a good prompt to tell it what to do, and include the retrieved documents. Let’s use a standard prompt for now:

from langchain import hub

prompt = hub.pull("rlm/rag-prompt")

example_messages = prompt.invoke(

{"context": "(context goes here)", "question": "(question goes here)"}

).to_messages()

assert len(example_messages) == 1

print(example_messages[0].content)The prompt looks like this:

You are an assistant for question-answering tasks. Use the following pieces of retrieved context to answer the question. If you don't know the answer, just say that you don't know. Use three sentences maximum and keep the answer concise.

Question: (question goes here)

Context: (context goes here)

Answer:Ok, now to put it all together. Now, in real life we’d probably want to use LangGraph at this point, and we’d want to think about including things like memory, ranking the results from the vector search, citations/references (“grounding” the answer), and streaming the output. But that’s all for another post! For now, let’s just do the most basic implementation:

question = "..."

retrieved_docs = vector_store.similarity_search(question)

docs_content = "\n\n".join(doc.page_content for doc in retrieved_docs)

prompt_val = prompt.invoke({"question": question, "context": docs_content})

answer = llm.invoke(prompt_val)

answerYou should get an answer similar to this:

AIMessage(content='Rokovoko is an island located far away to the West and South, as mentioned in relation to Queequeg, a native of the island. It is not found on any maps, suggesting it may be fictional.', additional_kwargs={'refusal': None}, response_metadata={'token_usage': {'completion_tokens': 46, 'prompt_tokens': 402, 'total_tokens': 448, 'completion_tokens_details': {'accepted_prediction_tokens': 0, 'audio_tokens': 0, 'reasoning_tokens': 0, 'rejected_prediction_tokens': 0}, 'prompt_tokens_details': {'audio_tokens': 0, 'cached_tokens': 0}}, 'model_name': 'gpt-4o-mini-2024-07-18', 'system_fingerprint': 'fp_54eb4bd693', 'id': 'chatcmpl-BaW3g2omlCY0l6LwDkC9Ub8Ls3V88', 'service_tier': 'default', 'finish_reason': 'stop', 'logprobs': None}, id='run--86f14be2-9c8f-43c9-ae89-259db1c640bd-0', usage_metadata={'input_tokens': 402, 'output_tokens': 46, 'total_tokens': 448, 'input_token_details': {'audio': 0, 'cache_read': 0}, 'output_token_details': {'audio': 0, 'reasoning': 0}})

That’s a pretty good answer!

Well, there you go, we covered a lot of ground in this post, but that’s just a very basic RAG. Stay tuned to learn about implementing a more realistic RAG in the next post!

Pingback: Exploring securing vector similarity searches with Real Application Security | RedStack

Pingback: Let’s make a simple MCP tool for Oracle AI Vector Search | RedStack